In April 2020, we led a webinar entitled Nonprofit Enterprise Management: Strategic Planning for Adverse Scenarios. As a nation, early in the COVID-19 pandemic we were struggling to understand the potential impact of an invisible enemy — a virus that brought the economy and society as we knew it to a screeching halt. The topic of the webinar centered on the idea that the nonprofit sector is where our communities and institutions go to solve problems. While the public sector debates and the private sector analyzes, the nonprofit sector takes action. Specifically, the webinar focused on operational and financial best practices that would help nonprofits formulate and sustain their important response to the crisis.

For the nonprofit sector, inaction is just not an option. The nonprofit sector mobilizes resources to address community needs as they occur and has proven to be one of the most effective agents of social change. But the world never gives us just one challenge at a time. In the midst of the global pandemic, the spotlight has been placed on another pair of invisible enemies to social progress — systemic racism and institutionalized biases.

In this paper, we attempt to tackle the leadership role that nonprofits can take in combatting systemic racism and institutionalized biases by engaging in best practices at the leadership, staff, and mission-engagement levels. There are no silver bullets that we can offer; instead, we are going to focus on how self-examination and being intentional in driving change can lead to better outcomes. The goal is to help identify blind spots and share best practices to help mitigate the root issues and establish periodic review of progress made.

There is an old saying that asks the question, “How do you eat an elephant?” The answer goes, “One bite at a time.” Much in the same way, the mammoth task of creating a diverse, equitable, and inclusive world can be tackled one bite at a time.

Current Landscape: How We Got to Today

Systemic racism and institutionalized biases are widespread and have served as obstacles to America’s ability to leverage one of its greatest resources: its diversity. While institutions have long recognized the need for diversity and the lack thereof, most have failed to adequately address the root cause of the lasting homogeneity of certain establishments. In other words, we see the results but have been unable to mitigate the causes. In this context, the current landscape can be broken down into three components: systemic racism, institutionalized biases, and what nonprofits are doing to change the status quo.

Systemic Racism

Racism has been a stain on our nation since its infancy. The hard truth is that, to date, racism has been a part of who we are as a nation. Throughout our history, we can find examples of institutionalized racism in the practice of human enslavement; lynching; Jim Crow segregation; discriminatory housing and lending laws; voter disenfranchisement; and unequal criminalization, policing, and sentencing that leads to mass incarceration. The consequences of these policies have yielded a material imbalance in our society among different demographics.

As a nation, we supported these practices while simultaneously proclaiming the “truth” that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights that among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness.” This quote from the Declaration of Independence represents the value statement and ideals of the United States of America; however, it is a value system that the nation has rarely lived up to from a racial equity perspective. There is a stark disconnect between our stated values and how our institutions treat certain people in the United States. This disconnect was baked into law, customs, and traditions from the birth of our nation and still exists today.

Institutionalized Biases

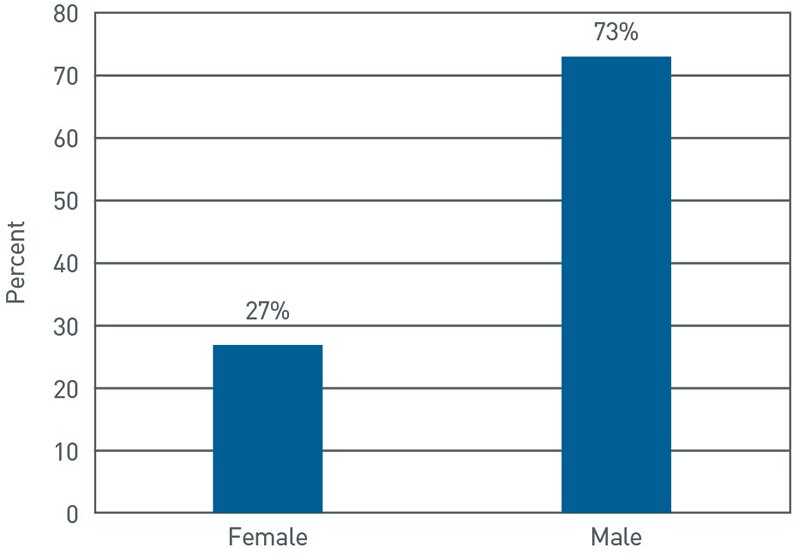

There are endless studies and research that establish and support that diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) improves outcomes for nonprofit and for-profit organizations alike. When we say DEI, many people default to thinking in terms of race or even religion; however, true DEI spans a number of different demographic considerations. Building a diverse and inclusive team of individuals across an expansive set of demographic factors, expanding from race and gender to include things like age, sexual orientation, education and/or experience, and even geographic background can help organizations to increase the likelihood of succeeding while avoiding many of the pitfalls that can come from a group of like-minded individuals engaging in a vacuum (or groupthink). Turning to two questions regarding diversity asked of nonprofit leadership, Charts 1 and 2 ask nonprofit leaders to self-identify and self-examine the diversity of their leadership teams.

Source: PNC; Data as of 8/31/20

View accessible version of this chart.

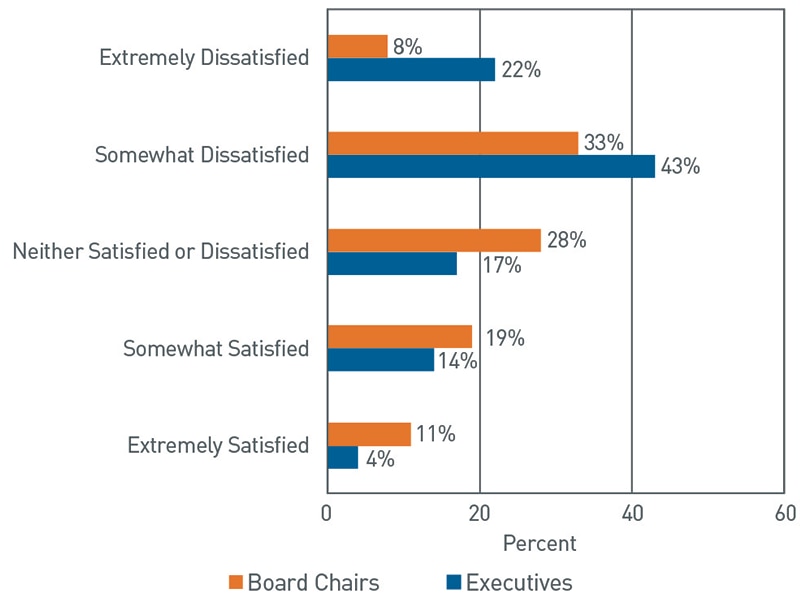

Chart 2: How Satisfied Are You with Your Board’s Racial and Ethnic Diversity?

Source: BoardSource

View accessible version of this chart.

The data might come as no surprise to many: Women are very much underrepresented on boards relative to their percentage of the population, and the majority of board chairs and nonprofit executives express some degree of dissatisfaction with their board’s racial and ethnic composition. This same exercise in understanding the demographic makeup of nonprofit leadership could likely be done for a number of different demographic factors and end up with similarly poor results.

This lack of diversity is driven in large part by institutionalized biases, manifesting in this example by like hiring like (whether consciously or unconsciously): A man gravitates toward hiring a man; people tend to hire others who look like them; and even the composition of the personal or professional network of the hiring manager can play a role in limiting the universe of diverse applicants. The examples are endless.

When taken as a whole, you end up with organizations with homogenous workforces of people who look the same, think the same, and act the same. And worse, this homogenous workforce, without intervention or an active intention to do otherwise, in turn hires a next generation that similarly perpetuates the cycle.

Nonprofit Organizations Are Not Sitting Idle

Many of our local and national institutions have made it clear that there is no place for racism or institutionalized biases in their organizations. With that said, the nonprofit sector has not been immune to these issues. Broadly speaking, there is a lack of diversity and inclusion from nonprofit leadership down to the employees and volunteers who execute the missions. Where there is diversity, there is still a lack of equity and inclusion. This shows up in a number of key ways:

- The experiences of diverse nonprofit leaders, who must skillfully navigate instances of overt discrimination, in addition to less overt subconscious biases;

- The difficulty nonprofit organizations serving communities or people of color face in fundraising; and

- The “silo-ing” of nonprofit organizations, especially local or community-focused, where employees, volunteers, and financial support tend to be from the community where the nonprofit organization is based, rather than from a wider geographic background.

Nevertheless, many nonprofit organizations have doubled down on their commitment to end systemic racism inside and outside of their institutions. Once again, nonprofits are rising to the challenge of solving big societal problems. As institutions within the nonprofit sector confront this challenge, they must first conduct self-examination and clearly identify shortfalls at the leadership level.

Leadership Level

The steps necessary to correct for these deficiencies in DEI have filled books, webinars, and more. Within the confines of this paper, we recommend two best practices:

- First, be intentional in recognizing any potential deficits in the diversity and inclusiveness of your team at the board, management, and volunteer levels; awareness allows you to take action.

- Second, commit to building the future pipeline of leadership in an intentional way that helps to ensure future generations represent a diverse and inclusive group of individuals.

Recognizing Potential Deficits

We promised self-examination as a major part of any actionable plan, and here it is:

- How diverse and inclusive is your leadership today?

- What kind of representation and inclusion do you have based on gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, religion, and background/experience?

- Would you say the demographic composition of your leadership is well-balanced, or are certain groups more highly represented than others?

- How does the composition of your leadership compare to the constituents or community(-ies) you want to serve?

These questions aren’t meant to be antagonistic, and there is nobody waiting in the wings to say “Gotcha” based on your answers. But, in the spirit of self-examination, how do you feel about your answers? In building your leadership team and thinking about your workforce, how intentional are you in building representation, equitable pay, health-related benefits, and overall satisfaction in the organization’s culture?

These days, it is hard to turn on the news without finding another example of a company that made a major misstep with regard to cultural (mis-)appropriation; has created or retained a product that has a racist history, connotation, or trope; or even delivered remarks that, regardless of their intention, failed to meet appropriate and inclusive standards. We won’t name them here or throw any stones; instead, we’d rather ask a question: How many of these events could have been avoided if a diverse leadership team was involved?

Demographics are changing, and, with technology, people in the world are closer to each other than anyone could have imagined. Most are familiar with the old adage, “trust can take a lifetime to build, but only a moment to lose.” In this modern world, consider how much more true that statement can be when anything has the potential to go viral and spread around to your constituents, your community, your donors, and the world at large.

If your organization is going to achieve its objectives in serving this changing landscape, it is important to make sure your leadership is built in a way that will enable it to serve today’s and tomorrow’s world.

Building the Future Pipeline

We would like to start here with a story. It was the early 2000s, and one of our colleagues, a Black male with a law degree fresh from a top-ranked school, was entering the banking world. New to his company, he was keen to meet his new co-workers. Soon enough, two of his co-workers, also Black, stopped to congratulate him on joining the ranks. After a few quick minutes, his new co-workers said they should go back to their desks. In their words, “they wouldn’t want others to think the three Black employees were up to something.” Our colleague looked around and saw others were starting to look at them; worse, a White employee walked by and said, “What are you three plotting?” Whether or not the employee was “just trying to make a joke,” they committed a microaggression against our colleague, who then felt as if there was merit to the suggestion that he wasn’t able to congregate freely with others employees who looked like him.

Microaggressions, like the story above, can be unintended – but nevertheless are hurtful to the recipient. The response required is two part: an open forum for addressing these microaggressions as they occur and ongoing training to illuminate and mitigate these types of behaviors.

Thinking about your own organization, is there anything about your culture that would give the impression that underrepresented team members cannot congregate freely? What effect would you expect that, or other microaggressions, to have on an employee at the start of their career? What would it do to their motivation, their productivity? And would they feel as if their job was just a job or something more like a career? Would they be proud to work there, would they want to stay, and, most relevant to this topic, would they want to work hard to grow into a leadership role with your organization?

Succession planning matters because, done well, it will help you to think strategically and explicitly about building the next generation of leadership that will help to carry the legacy of your organization and its mission into the future. In our colleague’s story, is there anything about your culture that would give the impression that underrepresented team members cannot congregate freely?

With this in mind, what is your organization’s plan for identifying, training, and promoting the next generation of leadership? A couple of best practices we have seen include:

- Creating a “shadow board,” where the next generation of leadership is paired with the acting board. The shadow board provides fresh input and ideas and in exchange they get to see existing board members’ decision-making processes and gain valuable experience in the exchange.

- Be intentional about diversity and inclusiveness. Succession planning can be the point where new influences and ideas can bring positive change and progress to the mission. In profiling candidates for vacancies, it is an opportune time to consider, along with experience and personality, other aspects such as gender, age, culture, and, to the extent it is relevant, geographic location.

- When considering board candidates, is your network broad enough to include diverse candidates in your search, and if not, what steps can you take to broaden your network? If it is broad enough, is there any bias that might be preventing you from considering diverse candidates? There are numerous courses on unconscious biases that can help you to identify and mitigate the effect these biases have on the recruitment process.

- Similarly to point three, could your criteria be part of the problem? Consider looking objectively at board member “criteria” and consider revising those that might be inadvertently narrowing the universe of candidates, such as geographic location, annual financial contribution requirements, and other factors. Certain criteria might have a disparate effect on different demographic populations.

- Identify a strategy for how to network and cultivate a diverse and inclusive pool of potential board members before starting the recruitment process.

- Have a well-documented plan and commit to both following it and periodically reviewing it. As with most things, having a plan goes a long way toward forcing your organization to act.

In considering these best practices, what does your leadership pipeline look like for leaders you’ll need in five years? 10 years? 20 years? The reality is that tomorrow’s leaders need to be developed and trained today. With this in mind, organizations need to be intentional that the cohorts of future leaders they are developing today are diverse, inclusive, and representative of where the organization and its mission will be in the future. If you don’t give a diverse, inclusive, and representative group of future leaders the development time and learning experience they need, how else will they be ready in the future?

As an example, imagine your building is on fire. At that point, do you have time to make a fire escape plan and educate everyone on how to leave in a safe and orderly fashion? The obvious answer is no. You have to have a plan, practice the plan, and be ready for the future event (a fire), or it will be too late.

Your building might not ever catch on fire (we certainly hope not!), but your leadership will certainly turn over at some point: People don’t work or stay forever. When they retire or otherwise leave, you have to be prepared with new leaders ready and able to lead your organization into the future. This is where succession planning is essential, especially if your next generation of leaders will be diverse and inclusive.

Returning to our story, that young man with his law degree didn’t just experience the one microaggression. Over the course of a decade, he was pulled into meetings with Historically Black Colleges and Universities at the last minute as a token representative, he was told that, to paraphrase, “he was lucky to get where he was as a Black manager,” and, when he was promoted, the jobs had their position level (and compensation) meaningfully decreased despite increased responsibilities for the role.

He eventually left that first company and joined ours. He now leads an entire segment of our clients. On a selfish level, we are endlessly grateful for him; on an objective level, the original company lost a great leader out of its pipeline; finally and perhaps most importantly, on a human level, a leader had to overcome rather than be supported in his development. In the spirit of self-examination, ask yourself: Are you supporting your future leaders?

Staff or Volunteer Level

Both related to the idea of leadership succession planning and in the interest of all who work for your organization, regardless of their leadership potential, DEI at the staff or volunteer level is extremely important to the overall success of any organization’s DEI strategy. Put simply, your employees are often the foremost face of your organization. With that in mind, there are two things to consider:

- Are your employees representative of your organization, your community, your mission, and/or our country at large?

- Do your employees feel like you value them for who they are and that they can bring their true, authentic self to work each day?

Beyond the direct value that having a diverse and inclusive workforce brings to your organization, these have a direct impact on employees’ productivity, representation of your organization (with donors and/or the constituents and communities your organization serves), and retention (i.e., how long they stay with your organization). An example of this can be simple: If someone on your fundraising team feels marginalized or otherwise discriminated against at work, how committed do you think that person will be in meeting with your potential donors?

No one story can capture the collective experience, but there are certainly themes that have emerged. Marginalized employees have expressed some or all of these feelings in stories:

- Excellence: The feeling that I, but not others, must dot every “i” and cross every “t.” Mistakes are often not forgiven, and my actions may reflect on my entire identity group.

- Mentality: I have been taught that I must work twice as hard in order to be considered equal.

- Lack of Support: I do not feel as though I receive the same level of support as the previous person to occupy the job.

- Higher Climb: To ascend as a leader in an organization, I understand that I have to have more credentials (letters behind my name) than I would if I were a different race or gender.

- Isolation: I am often the only person of my race or gender in the room.

- Burdened: When I hear racially or demographically insensitive comments, I feel obligated to speak up; however, I worry that it may negatively impact my career opportunities.

- Confusion: When I’ve been treated poorly, not recognized, or ignored, I often wonder if it is because of my identity status.

- Self-determined: I am hesitant to ask for help because I do not want anyone to think I can’t do the job or that I’m undeserving. I want to prove I belong.

- Lack of Trust: While I have the title, I often lack the authority or autonomy to make decisions. I feel that I must run my decisions by someone else.

- Lack of Voice: When I offer input, it is quickly disregarded because only the input of the board members is welcome. Staff should simply execute as instructed with no questions asked.

Keeping in the spirit of self-examination, have you felt any of these personally? Have you seen this happen to others at your organization? You aren’t alone – while the world is certainly a better place than it was 100 years ago, there is still much room for improvement. While there is no one panacea to prevent these feelings, we recommend the policy of committing to endlessly listening, learning, and acting, both on your own and with your organization.

Mission, Operational, and/or Grant Making Level

It is important to start this topic by noting that this is a difficult subject to generalize. Nonprofit organizations span from religious organizations, community foundations, and higher education institutions to healthcare systems, animal shelters, and museums, among others. Some are focused on serving constituents or communities through their operations, while others are focused on funding these types of operations through grant making.

At this point, we’d like to pause and introduce another one of our colleagues. Her story begins in an underserved community, where, despite her being the top of her class and taking every advanced class and/or opportunity for education, her school being not highly ranked prevented her application from being considered at her top university choices. In her words, “The community didn’t get the investment that other communities have, and that hasn’t changed even today. If it doesn’t change, the cycle will continue to repeat.” For her, the result was her dreams, everything she had worked hard for academically and in her life, were put at risk by circumstances entirely outside of her control. While she had done everything possible to succeed, the system had failed to meet her halfway.

So how do we prevent the cycle from repeating, and how does this relate to nonprofit organizations? For purposes of this discussion, we’ll tackle this two ways: mission/operational scope and grant making.

Mission/Operational Scope

Nonprofit organizations are considered institutional pillars of a successful society. They curate the museums that share our history and culture, they educate our next generation of leaders, they are a lifeline to those in need of food or shelter, and they provide for our religious and spiritual needs – to name a few of the many ways that nonprofit organizations fortify our people and our communities.

Returning to the story of our colleague, a counselor at her school refused to accept no for an answer. The counselor reached out to the universities that had ignored our colleague and was able to convince them to give her a chance, to judge her on her achievements and her potential, not her circumstances. One of the universities said yes, and our colleague went on to graduate in her desired field, quickly rising to the top of her field and going on to earn and add three more sets of credentials (each significantly difficult to obtain). Meanwhile, she was recruited by a top consulting firm and successfully launched her career.

Connecting back to nonprofit organizations, consider how successful your organization is in serving all of the constituents and community(-ies) related to your mission. There are two important lessons to take away from this story:

- First, reaching every part of the community – every part of town, every demographic, and every person that needs help.

- Second, building the connections, network, and resources to serve your constituents and community.

In our colleague’s story, the college counselor is analogous to a nonprofit organization: The counselor connected the underserved community (specifically, our colleague) to the resources she needed (a higher education institution). For this to work, the counselor had to be in the underserved community and to have the connection with the college to make the case for our colleague.

Much in the same way, nonprofit organizations should consider how they are uniquely qualified to serve as the bridge between underserved populations and the resources they need. In this way, nonprofit organizations can help advance DEI by helping underserved populations to gain access to education (e.g., test preparation services or college admissions outreach), inspiration (e.g., museums), healthcare (e.g., increased community outreach programs), and more. Every organization’s ability or approach to helping advance DEI will be different, but, regardless, it is the intentionality and results-focus of committing to making a difference that matter most. Keeping with the theme of self-examination, what is your organization doing to help make sure no part of the community is left out?

Grant Making

One of the well-discussed weaknesses in the world of grant making is the difficulty that organizations serving underserved or minority communities face in fundraising. This has been experienced from both sides of the equation: First, fundraisers that are minorities face difficulty in fundraising; second, nonprofit organizations that seek to serve minority and/or underserved communities tend to have more difficulty in successfully appealing to donors who don’t have similar demographic (e.g., race) or geographic (e.g., same community) characteristics.

Pausing here to return to our colleague’s story, unfortunately her difficulties didn’t end with her college application process. Fast forward a number of years, and she came to work for a manager who, to put it mildly, wasn’t the best. Over the course of her time with that manager, he did a number of things that are inexcusable; however, two remain top of mind for her to this day:

- When reviewing the resumes and applications for an open position, she overheard him making an inappropriate comment to another employee. The name on the application was a traditional African name, so the manager decided to make an offhand remark about how hard they could potentially work this candidate, which tied back to our nation’s history with slavery. Worse yet, the candidate never received an interview.

- When a female co-worker left the company to take a different job, citing “she wanted to achieve a better work-life balance,” the manager made the comment to several male team members that, “Oh, she’s a woman; she is just leaving to go start a family.”

This manager was supposed to be a leader, and yet he failed our colleague and all of her co-workers. These examples epitomize the struggles that both minority fundraisers and minority-focused causes face when fundraising: judged on their name, their gender, or other intrinsic demographic characteristics, rather than on their merits. Sometimes these are the result of unconscious biases, where someone doesn’t recognize the bias of their actions; other times, worse, they are the result of conscious biases. The former might be remediated through training, but the latter has no place in the modern workplace.

If your organization engages in grant making or otherwise allocating distributions to nonprofit organizations and their representatives (i.e., fundraisers), there are a couple of things that you can do to help prevent unintentional biases in your process.

- Consider your grant-making process: would you say your process relies more on subjective or objective criteria? While some subjective criteria can be beneficial, it is harder for subconscious biases to affect objective criteria. Creating a written process for grant applications that finds the appropriate balance between subjective and objective criteria appropriate to your grant-making objectives can help to provide each grant applicant an equal chance.

- Examine your application questions and/or grant-making rules (e.g., excluding sports-related nonprofit organizations) for potential blind spots. We used the example of sports-related nonprofit organizations because they frequently show up as an exclusion in many grant-making processes. While it might seem harmless, a number of nonprofit organizations serving minority communities focus on sports-based activities to engage children. Through this exclusion, many of these organizations can experience difficulty in supporting their mission. As a related note, having a diverse and inclusive board can help to identify more of these potential blind spots.

- To the previous point, make sure your grant-making selection committee is diverse, inclusive, and representative of the range of individuals, communities, and causes that you want to support. Whether that is your board, a separate committee, or a diverse group from your community that you engage to help, this approach can help to increase the likelihood that biases are removed from your grant-making process.

Returning to the story of our colleague, she decided that, among other things, her manager and her experience at her old company had made her job untenable. It wasn’t a place she wanted to work and grow her career, so she left. She now leads an entire client segment for our business and has committed significant amounts of her time to helping children in underserved communities to break out and be successful. She is one of our best leaders and a true example of determination and character. The company that lost her lost one of its best employees because the company allowed a manager with clear race and gender biases to exist unchecked. It is another example where a leader had to overcome despite her environment, rather than being supported by their environment. We hate the path she had to endure to get here, but we consider ourselves lucky to have her as a leader on our team.

Conclusion

At the end of the day, the biggest takeaway we would share is that racism and other biases are detrimental: They can affect employee productivity and retention, they can affect the mission (not serving people, communities, or causes that need it), and they can affect the efficacy of grant making (i.e., biases causing a grant maker to miss funding worthy causes).

Racism and other biases don’t belong in the home, the workplace, or the community. They won’t disappear overnight, but returning to the analogy of “eating an elephant,” if we all commit to being intentional in our self-examination and in striving to listen, learn, and act, we can tackle this problem together, “one bite at a time.”

We welcome the opportunity to engage further and share what PNC is doing to improve the DEI efforts for our teams. Our policy is to commit endlessly to listening, learning, and acting, both on our own and with the clients and communities that we serve. Please reach out to your PNC representative if you would like to continue the discussion.

About The Endowment & Foundation National Practice Group

The Endowment & Foundation National Practice Group builds on PNC Bank’s long-standing commitment to philanthropy and is focused on endowments, private and public foundations, and nonprofit organizations. Our group is structured to help these organizations address their distinct investment, distribution and capital preservation challenges.

For more information, please contact Henri Cancio-Fitzgerald at henri.fitzgerald@pnc.com.

Accessible Version of Charts

| Male |

73% |

| Female |

23% |

Chart 2: How Satisfied Are You with Your Board’s Racial and Ethnic Diversity?

| Board Chairs | Executives | |

| Extremely Dissatisfied | 8% | 22% |

| Somewhat Dissatisfied | 33% | 43% |

| Neither Satisfied or Dissatisfied | 28% | 17% |

| Somewhat Satisfied | 19% | 14% |

| Extremely Satisfied | 11% | 4% |