In response to examples in the news and client inquiries, we have prepared this paper to address the topic of nonprofit borrowing. For sake of clarity, we will start by identifying the two most common approaches: borrowing from an endowment and borrowing against an endowment. As a preface, it is important to note that many endowments, especially those with restricted funds, will not easily be able to engage in either method; furthermore, the charter, investment policy statement, or other policies may also prevent borrowing in any form. We are not able to give legal advice as to the feasibility of borrowing, and suggest an organization consult with its legal services provider before taking any action.

Why are nonprofits borrowing?

Simply put, nonprofits’ budgets are increasingly strained due to the increasing needs of the communities and missions that the nonprofits serve. There are just not nearly enough resources to address every inequity, every need, and every cause. Volatility and unpredictability of fundraising, in turn, can cause the potential for an operating cash shortfall if investment income is not sufficient to meet budgetary requirements. Further complicating things, donations are increasingly coming with donor restrictions attached. A study by the Stanford Social Innovation Review found that even the restriction on the reimbursement of indirect costs (typically 15%) is leaving nonprofits with excessive, and sometimes unexpected, bills that, in turn, can also lead to an operating cash shortfall.[1] Regardless of the cause, an endowment might borrow to make up the shortfall.

A second major reason for a nonprofit to borrow is to fund large-scale, long-term capital projects. These projects could include a new building, major renovations, or new equipment[2], and would likely need to be funded (at least partially) through borrowing. The loan or debt, in most cases, would have to be paid for through a combination of donations, investment income and operating income, if applicable. The major issue with this is that, given donations and investment income streams are not adequately predictable, nonprofits without substantial operating income sometimes have to pay a higher rate of interest (meaning higher cost of borrowing) than a comparable (with regard to leverage), for-profit entity would pay.

Borrowing against an Endowment

The first option that we will explore is borrowing from a lender using collateral. As we discussed above, the rate of interest on a loan is often determined by the perceived riskiness of the loan and the strength of the organization’s financials (both balance sheet and profit & loss). The perceived riskiness of the loan can be affected by whether the loan is secured (by specific assets of the borrower) or unsecured (without specific assets pledged). An example of this would be an organization that pledges a portion of its endowment being able to borrow at a lower rate of interest than if it does not pledge its endowment. Factoring into the perceived riskiness is the borrower’s financials: on the balance sheet side, this relates to restricted assets, unrestricted assets, and liabilities; on the profit & loss side, this refers to whether the organization runs a net income surplus (income greater than expenses) or net income deficit (expenses greater than income)[3]. An example of this would be that an organization with substantial unrestricted assets, little to no liabilities, and running a net income surplus would be able to borrow at a lower rate of interest than it would be able to if the same organization had limited unrestricted assets, high liabilities, and ran a net income deficit.

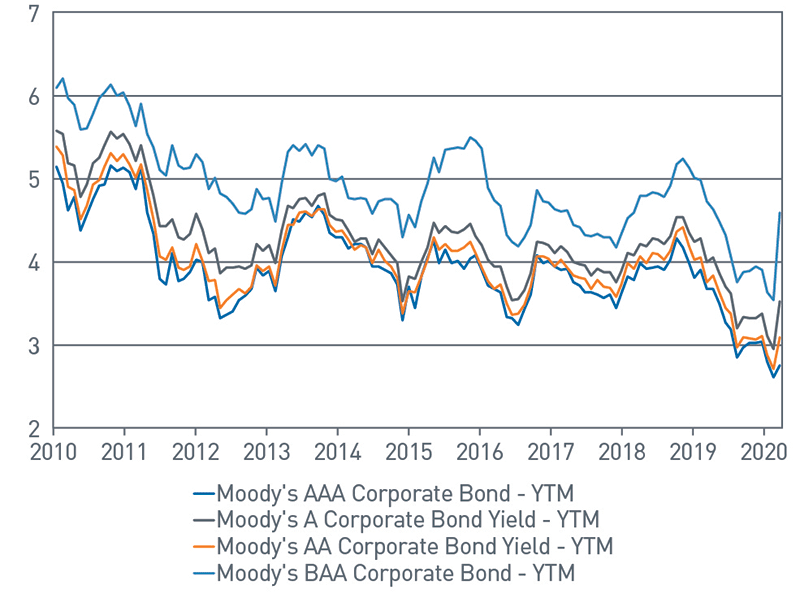

Borrowing using collateral generally takes two forms for nonprofits: the first is done by participating in a government (local, state or federal) guarantee program[4]; the second is done by pledging the assets of the nonprofit or of the endowment as collateral should the borrower default on the loan. This method is called “credit enhancement,” and its effect can be seen in the chart below. The difference (spread) between borrowing at a Moody’s credit rating of AAA and at a Moody’s credit rating of BAA can range from 1-2% to nearly 5% (although a 5% difference is extremely rare). Credit enhancement (through guarantee or collateralization) essentially provides the borrower with the ability to borrow at a higher credit rating, meaning at a lower rate of interest, than they would have been able to without securing the loan. A lower rate of interest means that the organization will have a lower cost of borrowing; this, in turn, helps to increase the likelihood that the organization will be able to repay the loan in full and on time.

View accessible version of this chart.

Borrowing from an Endowment

The second option that we will explore is borrowing from an organization’s endowment. The advantage of this approach is that it is sometimes, assuming that there are not restrictions on the pool of assets, easier to get “lender approval” (meaning that the board approves the loan). From here, there are two schools of thought with regard to setting the rate of interest on the loan.

The first policy is to charge the same rate of interest as the return target for the endowment. Using simplified math, an example of this would be adding a spending policy of 4%, inflation of 2%, and management (overhead) fees of 0.5% to determine a 6.5% rate of interest on the loan.

The second policy is to borrow using a rate of interest that is on par with similar duration securities in the fixed income portion of the endowment’s portfolio. An example of this would be matching the rate of interest on a 15-year loan with the yield to maturity on a 15-year fixed income index.

With both methods above, there are two major concerns with borrowing from the endowment: first, that it reduces diversification in the portfolio; second, depending on the size of the loan relative to the size of the endowment, there might be concentration risk. The upside is that the consequences of defaulting on the loan are internal, meaning that the lender does not come after assets or other forms of recompense. The endowment would still lose the remaining principal of the loan, but there is also the potential for greater flexibility around repayment grace periods to prevent that scenario.

It is important to note that, broadly speaking, borrowing money from an endowment reduces the liquid assets of the portfolio available for distribution per the annual spending policy. There are also drawbacks to both of the methodologies discussed above: in the case of borrowing at the portfolio’s targeted return, the interest rate might be higher than what the borrower would pay from another lender (suggesting it might be better to borrow against the endowment); in the case of borrowing at an index determined rate of interest, which is likely to be lower than portfolio’s target return, the portfolio is subject to a higher degree of duration risk.

Conclusion

Borrowing is always a difficult decision, and becomes even more complex when endowments enter into the equation. With that said, the endowment does have the ability to support the organization through serving as a lender or through collateralization. If it is not possible to secure a government guarantee for a bond issue, the collateralization of the loan with the endowment can help to lower the rate of interest on the loan (relative to an uncollateralized loan) and, unlike borrowing from the endowment, does not immediately take away from the liquidity of the fund. Alternatively, borrowing from the endowment allows more flexibility and less external consequences to paying (or failing to pay) back the loan. Ultimately, your organization’s leadership and board of directors are best positioned to determine the right choice for your organization.

For more information, please contact your Investment Advisor.

Accessible Version of Charts

Moody’s AAA Corporate Bond (MCBAAA-FDS)

As of 3/31/20

Source: FactSet Research Systems Inc., PNC.

| Date | Moody's AAA Corporate Bond - YTM | Moody's AA Corporate Bond Yield - YTM | Moody's A Corporate Bond Yield - YTM | Moody's BAA Corporate Bond - YTM |

| 4/30/2010 | 5.15 | 5.39 | 5.58 | 6.09 |

| 3/31/2011 | 5.13 | 5.3 | 5.54 | 6.04 |

| 3/30/2012 | 4.03 | 4.22 | 4.58 | 5.3 |

| 3/29/2013 | 3.89 | 3.95 | 4.2 | 4.77 |

| 3/31/2014 | 4.3 | 4.38 | 4.5 | 5.03 |

| 3/31/2015 | 3.45 | 3.63 | 3.8 | 4.42 |

| 3/31/2016 | 3.72 | 3.77 | 4.03 | 4.89 |

| 3/31/2017 | 3.91 | 4.02 | 4.19 | 4.61 |

| 3/30/2018 | 3.78 | 3.92 | 4.08 | 4.59 |

| 3/29/2019 | 3.68 | 3.76 | 4 | 4.73 |

| 3/31/2020 | 2.76 | 3.09 | 3.53 | 4.59 |