At 5’1”, Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was small in stature, but her impact was enormous, as demonstrated in the exhibit “The Notorious RBG: The Life and Times of Ruth Bader Ginsburg.” Currently at the Maltz Museum of Jewish Heritage[1] in Cleveland, the exhibit is presented locally by PNC. It will provide a glimpse into Ginsburg’s nontraditional role and her effect on the law.

The exhibit takes viewers from Ginsburg’s upbringing in Brooklyn, N.Y., into her years as a law student and further through her career, and highlights her unprecedented impact on gender equality and financial independence for women.

“Justice Ginsburg was an advocate for all Americans, and especially women, which is why we felt it was important to be the presenting sponsor of this exhibit that honors her life,” said Pat Pastore, PNC regional president for Cleveland. “Her focus on equality aligns with PNC’s commitment to diversity and inclusion throughout the company.”

Though inequality still exists, women can climb the career ladder, work the same jobs as men, buy a house, obtain a credit card and have their own bank account. The idea that these things were nearly impossible not long ago might seem outrageous, but in fact, it was not until 1988 through the Women’s Business Ownership Act that women were able to obtain a business loan without a male cosigner.

All of this might have remained impossible if it weren’t for Ginsburg’s hard work.

“She was born at the time when gender discrimination was embedded into society,” said David Schafer, managing director of the Maltz Museum. “Many opportunities for women were not available.”

A Champion for Financial Independence

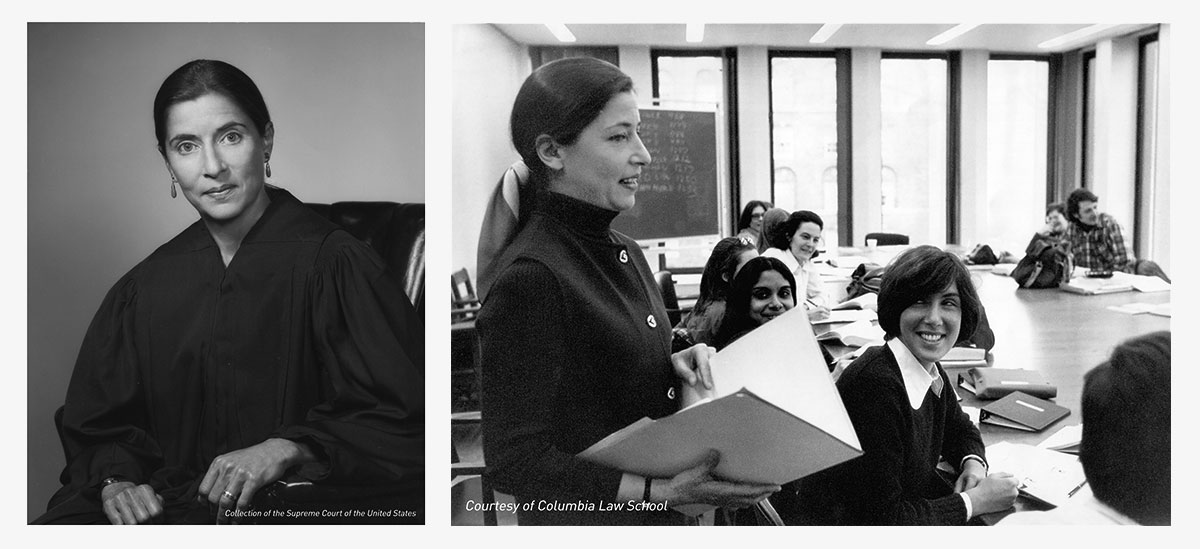

Ginsburg graduated from Columbia Law School in 1959 at the top of her class, but she still had a hard time finding a job. So, in 1963, she became a professor of law at Rutgers University School of Law.

Rutgers paid her less than male professors and in 1970, she filed a class-action lawsuit against Rutgers for equal pay. Winning that case marked the beginning of her fight for equal rights.

Ginsburg would eventually win five of the six equal rights cases she argued before the Supreme Court, starting in 1971 with Reed v. Reed. In that case, a woman wanted to administer her deceased son’s estate, but the law expressly gave preference to men. Reed was separated from her son’s father.

“Laws which disable women from full participation in the political, business and economic arenas are often characterized as protective and beneficial,” Ginsburg argued. “The pedestal upon which women have been placed has all too often, upon closer inspection, been revealed as a cage.”

The following year, Ginsburg became a professor of law at Columbia and co-founder of the Women’s Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union.

“This is when she began developing thoughtful strategies to change the law,” said Rebecca Haywood, managing chief counsel for PNC. Haywood cited Ginsburg’s work on the Supreme Court, as a litigator and with the ACLU, as inspiration for her own pursuit of a career in law. “Justice Ginsburg’s legacy involves not only her tireless pursuit of equality, but her perseverance under the most challenging of circumstances. And she helped many of us see and believe that regardless of our individual circumstances, we can achieve success at the highest levels,” said Haywood.

In another case, Frontiero v. Richardson, a female U.S. Air Force Lieutenant named Sharon Frontiero had been denied the ability to claim her husband as a dependent, even though men were able to claim their wives as dependents. Ginsburg argued that a woman’s work is just as important to the family as a man’s work. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of Frontiero, striking down the military’s unequal benefits for men and women.

“She was saying that we, as women, need to be given the same benefits that men have and should be treated equally under the law,” said Haywood.

Financial Equality for All

Ginsburg didn’t focus solely on women’s rights. In 1973, she represented a man named Stephen Wiesenfeld, whose wife had died during childbirth. His wife had been a working teacher who paid into social security, but Wiesenfeld was denied her benefits. At the time, the Social Security Act provided benefits to widows and children based only on their husbands’ earnings. Ginsburg argued that denying fathers benefits because of their sex was unconstitutional and another form of discrimination, and she won. The ruling was important in demonstrating that discrimination on the basis of sex harms us all.

Over the years, Ginsburg became known as an equal rights crusader who, through thorough research and thoughtful writing, changed opinions.

“Feminist groups often got angry with her for not taking cases that sizzled, but she was interested in permanent change,” Schafer said. “She was strategic in building layers of gender equality.”

In 1993, President Bill Clinton nominated Ginsburg to the Supreme Court, where she continued her work for equality.

In 1993, President Bill Clinton nominated Ginsburg to the Supreme Court, where she continued her work for equality.

In 2007, the Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. case came before the Supreme Court. Lilly Ledbetter was arguing for equal pay for her work at Goodyear. The Supreme Court ruled her claims were barred by the statute of limitations. Ginsburg read her dissent from the bench.

In 2007, the Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. case came before the Supreme Court. Lilly Ledbetter was arguing for equal pay for her work at Goodyear. The Supreme Court ruled her claims were barred by the statute of limitations. Ginsburg read her dissent from the bench.

“Ledbetter’s readiness to give her employer the benefit of the doubt should not preclude her from later seeking redress for the continuing payment to her of a salary depressed because of her sex,” Ginsburg wrote.

In 2008, President Barack Obama signed into law the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act.

In 2008, President Barack Obama signed into law the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act.

In 2013, the Supreme Court decided the Shelby County v. Holder case, in which it struck down a provision of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that determined which voting jurisdictions needed preclearance by the federal government before changing voting laws. The provision had increased minority voter turnout over the years. Ginsburg dissented.

In 2013, the Supreme Court decided the Shelby County v. Holder case, in which it struck down a provision of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that determined which voting jurisdictions needed preclearance by the federal government before changing voting laws. The provision had increased minority voter turnout over the years. Ginsburg dissented.

“Throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet,” Ginsburg wrote.

Schafer regards Ginsburg’s dissent in Shelby County v. Holder as her most significant.

“She was passionate,” said Schafer. “Her dissents were always stated in such powerful terms.”

“Justice Ginsburg took the necessary steps to fight for what she believed in, even if it wasn’t the popular opinion at the time,” Haywood said. “And society has benefited.”